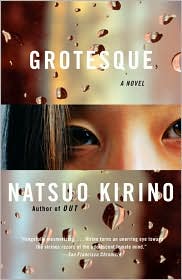

In an earlier post, I mentioned that Grotesque was on a fantasy reading list related to sleeping beauty. Due to availability, I ended up reading the list in reverse order, so Grotesque was first on the list instead of last. For those of you who have read Kirino's Out, this second translated novel will be a bit of a disappointment, however it was still an enjoyable read. The disappointment wasn't comparable, for example, to the disappointment of reading Donna Tartt's The Little Friend after loving The Secret History.

On the surface, Grotesque is the story of how two young Japanese students from an elite high school both end up working as prostitutes and dying similarly gruesome deaths. However, Kirino tells a more complex tale of how jealousy and hubris twist the way different characters see themselves and the world around them. Kirino effectively accomplishes this by allowing several characters to speak in the form of letters, court transcripts, and diaries as well as through first person narrative. What emerges is a series of sad stories in which nearly every character is the victim of their own illusions.

The central character is Yuriko, a beautiful girl and skilled seductress from a young age. She becomes a prostitutes and is the first murder victim. Her sister, who is never named, is the main narrator throughout the novel. When she steps aside, it is only to give the reader glimpses into documents written by or describing other characters. The sister suffers from tremendous jealousy of Yuriko and develops a talent for maliciousness and misinterpretation from a young age. Yuriko, in contrast, seems to be an honest observer. She is keenly aware of how she is perceived, both at the height of her beauty and attractiveness and as she ages into an overweight, garishly painted, unwanted streetwalker.

From this reader's point of view, one of the most redeeming features of this book is the fact that Kirino takes on so many different voices and view points in telling the story. Most of the narrators, including the anorexic classmate, tell colored tales designed to put themselves in the best light while more or less trashing everyone else around them. With the exception of Yuriko, no one takes responsibility for the path their life takes, preferring instead to blame any person or circumstance they can think of. There is predictably irony in the fact that the virgin (the unnamed sister) is untrustworthy while the whore (Yuriko) seems to tell an honest story. In the end, however, this is less the story of two murdered prostitutes than a story of how our own warped self-images can shape our lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment